When it comes to HIV infection, the need for improved diagnostic care couldn’t be more evident. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 29% of HIV-infected persons in this country are unaware of their HIV status. CDC surveillance data also indicate that 37% of persons who test positive for HIV develop AIDS within a year after their diagnosis, meaning that many individuals likely remain unaware of their infection for several years, potentially putting their own health—and the health of others—in jeopardy. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH) statistics mirror those of the CDC: approximately 25% of HIV-positive New Yorkers learn that they are infected with HIV at the time of an AIDS diagnosis.

Another central concern is the fact that between 27,000 and 30,000 of blood tests conducted annually at publicly funded testing sites are positive for HIV antibodies. However, approximately 31% of those who test positive do not return to anonymous testing sites to receive their results.

In light of these statistics, public health officials, clinic directors, and individual clinicians have been involved in initiatives to make confidential HIV testing a routine part of medical care with the use of new diagnostic technologies, including rapid HIV assays. These assays have been developed to make point-of-care (POC) HIV testing feasible and to greatly reduce the number of persons who do not learn their HIV status by providing immediate results. “When it comes to these assays,” Dr. Kevin Armington said in his introductory remarks, “we live in an instant gratification society. If people can get a negative or preliminary positive result in twenty minutes, that’s the test most people are going to want. The numbers suggest that a lot of people change their mind about learning their results during the older one- to two-week waiting period. This is something we can improve with same-day testing.”

| About Rapid HIV Testing | Top of page |

There are four rapid HIV tests approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Two of these assays are designed to be POC tests, in both medical and non-medical settings. They can also be performed in separate laboratories after a specimen has been obtained.

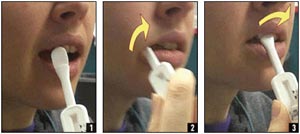

Figure 1. Performing an OraQuick Rapid Advance Antibody Test

A sample OraQuick Rapid Advance antibody test is shown here (image 1). To collect a specimen for the test, either touch the collection loop to a fingerstick blood droplet (image 2) or use standard phlebotomy collection procedures for whole blood with the following test tubes: EDTA, Sodium Heparin, Sodium Citrate, or ACD Solution and dip the collection loop into the test tube (image 3). Five microliters of whole blood should adhere to and fill a single collection loop (image 4). Insert the loop and stir the specimen in the vial of developer solution (image 5). The OraQuick device is inserted into the developer vial where it remains until the results are read (image 6). Test results must be read no sooner than 20 minutes but no later than 40 minutes after the device is added to the developer solution (image 7).

Source: Orasure, Inc.; U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The first assay—which Dr. Armington referenced often in his March 2005 PRN lecture—is Orasure’s OraQuick Advance, which can be used to detect antibodies to HIV-1 and HIV-2 in whole blood, oral fluid, and plasma. Results are available in 20 minutes. OraQuick Advance is the only FDA-approved rapid assay that can be used with oral fluid. An earlier (and still available) version of the OraQuick assay, the Oraquick Rapid HIV-1 Antibody test, can only be used on whole blood or plasma samples collected via finger stick or venipuncture, and only to look for antibodies to HIV-1.

There also is Trinity Biotech’s Uni-Gold Recombigen, useful for the detection of HIV-1 antibodies in serum and plasma. Results using Uni-Gold Recombigen are available in ten minutes. MedMira Labs, a Canadian company, has FDA approval for Reveal G2, for detection of antibodies to HIV-1 in serum and plasma. Results are available in five minutes using this assay. Finally there is Bio-Rad Laboratories’ Multispot assay, approved for the detection of both HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies in serum and plasma. The Multispot assay differentiates HIV-1 from HIV-2 antibodies, and produces accurate results after 15 minutes.

Any medical office, clinic, or organization that performs a rapid HIV test to provide results to patients is considered to be a laboratory under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA). As a result, all laboratories must comply with the regulations of the CLIA Program and with any applicable state requirements.

Sale of rapid HIV tests is restricted to clinical laboratories that have an adequate quality assurance program where persons who use the test will receive and use the instructional materials provided with the tests. The FDA also requires that persons tested with rapid assays receive the "Subject Information" pamphlet provided with the test. Details about other restrictions that apply to the rapid HIV tests are outlined in the package inserts provided with the test kits.

Currently, two of the available rapid HIV tests are “waived” and two are categorized as “moderate complexity” under CLIA. CLIA requirements for laboratories—any medical office, clinic, or organization performing rapid HIV testing is considered to be a laboratory—differ depending on the category and complexity of the test.

The OraQuick Advance and Uni-Gold Recombigen assays are CLIA-waived tests when used with whole blood or oral fluid. For waived tests, there are no federal requirements for personnel, quality assessment, or proficiency testing, although the tests must comply with state and local regulations and laws. In turn, waived tests can easily be done in traditional laboratories or clinical settings, and also in settings such as doctors’ offices, HIV counseling and testing sites, mobile vans, and health fairs. To perform only waived tests, an organization must obtain a certificate of waiver from the CLIA program (or be included with a CLIA-certified laboratory under a multiple site exception) and follow the manufacturer’s instructions for the test procedure.

In New York State, this waiver must be obtained from the New York State Department of Health Wadsworth Center as a Limited Service Laboratory. For information on requirements and application procedures, clinicians may contact the Clinical Laboratory Evaluation Program (CLEP) at (518) 485-5378 or visit the website at: http://www.wadsworth.org.

The Reveal G2 and Multispot assays are both categorized as moderate complexity under CLIA. Because they must be performed on serum or plasma, the specimen must be centrifuged and these tests are best suited for a more traditional laboratory.

| The OraQuick Advance Assay | Top of page |

Figure 2. OraQuick Advance: Oral Fluid Collection

OraQuick Advance allows for the collection of oral fluid specimens by swabbing gums with test device. Gloves are optional, given that the waste is not biohazardous.

Source: Orasure, Inc.; U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The OraQuick Advance assay, if using whole blood samples, boasts a sensitivity of 99.6% and a specificity of 100%, although the specificity decreases as the prevalence of HIV in the community decreases. Oral fluid samples are associated with a sensitivity of 99.3% and a specificity of 99.8%. If plasma is used, the sensitivity is 99.6% and the specificity is 99.9%.

To conduct the OraQuick Advance Assay, a vial of developer solution is placed in a plastic stand. The reusable stand holds the test device at the correct angle to ensure accurate test results. If whole blood is to be used, a drop of blood is collected with a small plastic loop from the finger stick—or from a collected tube of blood—and stirred into the vial of developer solution. The OraQuick device is then inserted into the developer vial where it remains until the results are read (see Figure 1). If an oral sample is used, the tip of the test device itself can be used to swab the gums and then inserted into the developer vial (see Figure 2).

Test results must be read no sooner than 20 minutes but no later than 40 minutes after the device is added to the developer solution.

The test result is read directly from the OraQuick device (see Figure 3). If only one reddish band appears at the control (C) location the test result is negative for HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies. If two reddish bands appear, one at the control (C) location and one at the test (T) location, the test is “reactive”—that is, a preliminary positive for HIV-1 or HIV-2 antibodies. However, if no band appears at the C location, if any bands appear outside the C or T locations, or if a pinkish-red background appears in the device window, the test is invalid and must be repeated (or followed up using a standard EIA assay).

Because the OraQuick test includes an internal positive control, it is not necessary to run external control specimens with each test. However, positive and negative external controls should be run by each new operator prior to performing testing on patient specimens, whenever a new lot or new shipment of test kits is used, if the conditions of testing or storage (e.g., temperature) fall outside the range recommended by the manufacturer, and at periodic intervals specified in the laboratory's quality assurance program.

Test kits have a shelf-life of eight months. False positives are possible and have sometimes been associated with conditions such as hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections, rheumatoid factor, Epstein-Barr virus infection, and have been documented in multiparous women. Invalid tests may be repeated or tested using EIA and/or Western blot. And most importantly, reactive results should be considered preliminary and require confirmatory Western blot testing.

More information on the OraQuick Advance test can be obtained through OraSure’s website (http://www.orasure.com).

A description of the testing process using the Uni-Gold Rocombigen assay is highlighted in (Figure 4).

| Implementing Rapid HIV Testing | Top of page |

Figure 3. Reading and Interpreting an OraQuick Rapid Advance Antibody Test

Six possible results using the OraQuick Advance antibody test. A nonreactive test will yield a line in the control (C) area and no line present in the test (T) area (Image 1). A nonreactive test result should be interpreted as negative for HIV-1 antibodies. A reactive test will yield a line in the control area and a line in the test area (Image 2). A reactive test result should be interpreted as a preliminary positive for HIV-1 antibodies and must be confirmed. Also shown here are three examples of invalid test responses (Images 3-5), which require that a second test be performed. A weakly reactive test will yield a line in the control area and a weak line present in the test area (Image 6). Follow-up testing is recommended to confirm an initial weakly active result.

Source: Orasure, Inc.; U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The successful implementation of rapid HIV testing does not begin with the assay itself, but rather with pre-testing counseling. “Everything that’s required for standard EIA and Western blot is required for rapid testing,” Dr. Armington said. “Pre-test counseling still needs to be done.”

Pre-test counseling should involve person-to-person communication, although some information can be provided in a written overview. “Those receiving the test should receive basic information,” Dr. Armington said, “which should include information about what HIV is and its relationship to AIDS; how the virus is transmitted; the various tests, including rapid tests, available to diagnose the infection; the discrimination issues some people face; and the need for informed consent reporting, and partner notification.” He also explained that forecasting questions are important before rapid HIV testing. “It’s important to know if the person being tested has a plan in place if the result is positive. It’s especially important if someone has engaged in a lot of risk behaviors but hasn’t really thought about what they might do if the result is positive. It’s also important for people being tested to know that a positive result is very different today than it was years ago. The medical management of HIV has improved dramatically and those being tested need to know this as a component of pre-test counseling.”

With the conclusion of the pre-test counseling, the collection of informed consent, and the results of the assay available, it’s time to deliver the news to the individual receiving the test.

A negative result using a rapid HIV test should be considered definitive. However, it is important to discuss the window period associated with HIV testing. According to an article in the December 2003 issue of The PRN Notebook, based on a lecture delivered by the CDC’s Dr. Bernard Branson, the OraQuick assay is capable of detecting HIV antibodies in as little as 14 days after infection is established. But for individuals who may have had a recent exposure, there is a need to recommend retesting in three months. If acute HIV infection is suspected, PCR or bDNA testing may also be warranted.

Figure 4. Performing a Uni-Gold Recombigen HIV-1 Antibody Test

Trinity Biotech’s Uni-Gold Recombigen, a CLIA-waived test, is useful for the detection of HIV-1 antibodies in serum and plasma (Image 1). Add one drop of serum or plasma to well (Image 2). Add four drops of wash solution to well (Image 3). Read results in 10 to 12 minutes (Image 4).

Source: Trinity Biotech; U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“It’s tempting just to send a patient on his or her way, upon testing negative, with instructions to repeat the test in three to six months,” Dr. Armington pointed out. “However, this is an excellent opportunity that shouldn’t be lost, to provide the patients with risk-reduction counseling and to make referrals. Plus, some patients may view a negative result as an endorsement of prior risky behavior. If you identify a problem, such as somebody practicing really unsafe sex, he or she may need therapy or need information on how to protect themselves better. There are referrals to be made here. The same holds true if there are drug or alcohol issues.”

The situation becomes a bit more complex when providing preliminary positive results. As Dr. Armington testified, it is vital to explain what a preliminary positive diagnosis means and to discuss the likelihood of infection based on risk. “Patients should be informed that a very small number of people who are HIV negative may have a rapid test that is reactive,” he said, referring to the one to two false positives that can occur among every 1,000 positive rapid HIV test results. “At Callen-Lorde, we explain that a follow-up test is needed and arrange for the test to be performed before the patient leaves the clinic. We also explain the likelihood of infection based on risk. If the patient reports that he or she has not engaged in unprotected sex or sharing drug equipment, we explain that there is a chance that the result could be false positive. But since there may be risks that they’re not remembering, don’t know, or don’t want to share, we explain that there’s a chance that he or she could be infected.”

The results of the Western blot, once returned from the laboratory, are definitive in the event of a positive rapid HIV assay. In the event of a negative result, the CDC recommends a repeat confirmatory test to rule out the possibility of sample mix-up or evolving seroconversion. “It also might be worthwhile to consider other diagnostic testing, such as hepatitis A, B, or C screening, rheumatoid factor, EBV infection, and also HIV PCR if there was the possibility of a recent exposure to HIV,” Dr. Armington said. “And, again, this is an ideal opportunity to offer further counseling and to provide referrals.”

The most likely scenario, after a preliminary positive rapid assay, is that the confirmatory Western blot will also be positive. “This makes for a difficult office visit,” Dr. Armington said. “It’s not easy to tell someone that they have a devastating diagnosis. I think the challenge here is to find an avenue to impart a little bit of hope to the patient. It can be helpful to offer reassurance on medical interventions and to highlight the advances made over the last 20 years. It’s also worthwhile considering baseline assessment testing and to offer referrals for emotional and concrete support services. Be prepared if a patient requires crisis intervention. Return to the forecasting questions that the patient answered before having the test—questions about what the patient would do next or who they would contact if the result were positive.”

| Challenges to Clinicians | Top of page |

Implementing rapid HIV testing requires planning. First, there is the issue of space to consider. “When a patient comes in for a test,” Dr. Armington explained, “they’re going to need a space to review the written materials, including the informed consent, and to receive the necessary pre-test counseling. It’s always possible to be creative about where in the office or clinic there might be space to do this.” Another factor to consider, he reminded everyone, is that the test kit must remain stationary throughout the processing time, requiring attention to where it is placed.

Staffing issues are also important. Dr. Armington explained that several elements of rapid HIV testing can be delivered by non-clinician staff. These include pre-test counseling, assuring informed consent and completion of other documents, and performance of the assay, including finger stick and oral swabbing. “Some clinicians choose not to be involved in the actual discussion of the test results, preferring to delegate this to trained staff,” he said. “It’s about figuring out what works for you.”

The time involved in counseling and testing is another factor that needs to be considered. Dr. Armington estimates that five to 10 minutes is required for pre-test counseling, five to 20 minutes is required for post-test counseling, and a five- to 20-minute processing time is required in between, depending on the assay used. “How best to utilize these times will depend on the practice,” he said. “Some clinicians may wish to see another patient while waiting for the results of the test, while others may wish to conduct a more comprehensive screening for other sexually transmitted infections. Many patients at Callen-Lorde have said that they’re happy to be worked up for other STIs while they’re waiting for the results.”

Charting and billing was also addressed by Dr. Armington. In terms of charting the test, “documenting as a SOAP note is suitable,” he said. “Be sure to document the amount of face-to-face time spent in a visit and on counseling, along with the nature of counseling.” With respect to billing, he commented that the visit should be coded as an office visit by using E/M codes on the basis of face-to-face time. “If your clinic or practice qualifies for multi-tiered Medicaid billing, you may be able to bill for the kit. If rapid testing is added onto a complete physical exam, code as a preventive office visit.”

| Health Behavior Change: A Counseling Strategy for Clinicians | Top of page |

Many modern-day health risk behaviors result from voluntary behaviors such as unhealthy eating habits; the use of tobacco, alcohol, or other drugs; and, when it comes to HIV and STIs, the failure to utilize safety precautions that are, for the most part, readily available. Health risk behaviors, once considered the result of faulty decision-making, impulsive behavior, or characteristic of psychosocial development, are now recognized as dynamic conditions evolving across the lifespan. “These are very difficult topics for many patients and providers to discuss,” Dr. Armington noted, “but they really are topics that should be explored with patients’ clinicians.”

One method of applying health behavior change counseling is through motivational interviewing. This technique, which came about in the 1990s, was designed as a brief, non-confrontational way of helping patients make changes in their behavior. The goal of motivational interviewing is to create a safe and supportive rapport with a patient, in order to facilitate their thinking about their behavior and whether or how they might go about making changes. The technique acknowledges that the idea of change can have both positive and negative connotations and takes both of these aspects into account.

Strategies of motivational interviewing—and health behavior change counseling—include the following: 1) Asking for permission to discuss a subject, such as the patient’s sexual activity. 2) Asking open ended questions. Clinicians should avoid using questions that will elicit a literal answer that obscures pertinent information. For example, clinicians should ask what a patient likes to do sexually, instead of providing a list of activities. “Listen to the language they use,” Dr. Armington said. “Some patients may not know what anal intercourse means. And don’t be embarrassed to speak the language being used by patients.” 3) Engage in double-side reflective listening. Listen for the underlying meaning of what is being said and then reflect it back to the patient. An example provided by Dr. Armington: “So I hear you saying that you are spending $200 a month buying this miracle juice, which is supposed to be an immune enhancer, yet every weekend you’re going out and challenging your immune system with all of these drugs. There’s an inconsistency here.” 4) Provide non-judgmental feedback. “Clinicians need to create the sense that they are supportive,” he explained further. “Reinforce important statements with reflective listening and support, such as nods and an encouraging choice of words and tone.” 5) Bring attention to discrepancies between present behavior and a patient’s broader health goals. 6) Avoid arguing and pressuring a patient into action. 7) Negotiate goals that are realistic and attainable. “Somebody who is never using condoms is not going to start using condoms 100% of the time by their next office visit. Let the patient set a realistic goal for him or herself, such as using condoms one weekend a month, at least initially. It may sound silly, but these things really are meaningful. The emphasis here is on collaborative discussion and recognizes that incremental change—anything that helps a patient move along the spectrum of behaviors towards healthy activities—is better than no change at all. It is essential to find out what’s really going on, because this is what clinicians really want and need to know.”

| References | Top of page |